Hidden amid the forest of high rise towers in the Taft area of Metro Manila looms the 225-foot tall back of a woman. A girl, to be truthful. She carries a heavy backpack, a water jug at her hip, and a child at her side. Atop her head is what scant food they could gather stuffed in a sack of rice, a school book tied to it securely. Her bare feet step into waters of uncertainty.

Archie Oclos’ mural Bakwit is arguably the tallest art piece created in 2019. The giant painting stretches over one side of the De La Salle College of Saint Benilde School of Design and Arts building and puts the spotlight on the plight of the humble Lumad, our indigenous population forever burdened with hardship brought about by the constant militarization, harassment, and bombing on their ancestral lands.

The mural, whether it intends to or not, also manages to thumb its nose at the established Philippine art market. Oclos, one of the Cultural Center of the Philippines’ 13 Artists Awardees, is an emergent and in demand contemporary artist with exhibitions both in and out of the country. His paintings command stunning prices among discerning art collectors, but many of his works can be found on the streets, to be beheld for free by any passerby. Bakwit, Oclos’ most astonishing work to date, is quite literally larger than life, priceless on the market, cannot be contained in any gallery, and impossible to possess.

The Philippine art scene and the Philippine art market share one long continuous navel. The artists, ever enchanted by the world around them that they seek to re-interpret unto a fixed medium, need patrons and collectors to buy their pieces so they can continue their work, unencumbered by the 9 to 5 grind. The wealthy patrons in turn purchase these works of art and display them proudly in galleries or private collection– lightning in a bottle, with a nifty price tag.

So while art fairs in recent years have made an event of moving outside of stiff galleries and into the relatively public spaces in the heart of a commercial district, the average Filipino is simply invited to be a sightseer into the playground of the affluent. While we take our Instagram shots of the exciting art pieces, the moneyed elite lap up works of the artists, especially the young and new, so they can watch their career with great interest as their works appreciate in value.

The collection of art among the wealthy is a cultural dog whistle that communicates a different level of sophistication for the collector. A rich person who collects sports cars is a braggart in a country steeped in traffic. If he collects designer clothes and expensive gadgets, he is a superficial show off. But if he collects art, then he has cosmopolitan tastes, an eye for the avant-garde, even possibly woke depending on the subject of the art he collects. Depoliticized, art can be used to deodorize controversy.

And what is the art scene without controversy? The shared navel of artists and art collectors make this dynamic extra complex. While some artists insist on creating progressive works that criticize the social status quo, their pieces go on exhibit in galleries with members in their board of directors directly involved in land grabbing or the burning down of farmers’ homes. Some collectors are tainted politicians or enabler cronies. The family of the deposed dictator are known avid art collectors as well.

The art scene follows the art market, and vice versa. So when a new breed of art collectors came to play at the turn of the millennium, so did Filipino contemporary art adjust to their tastes.

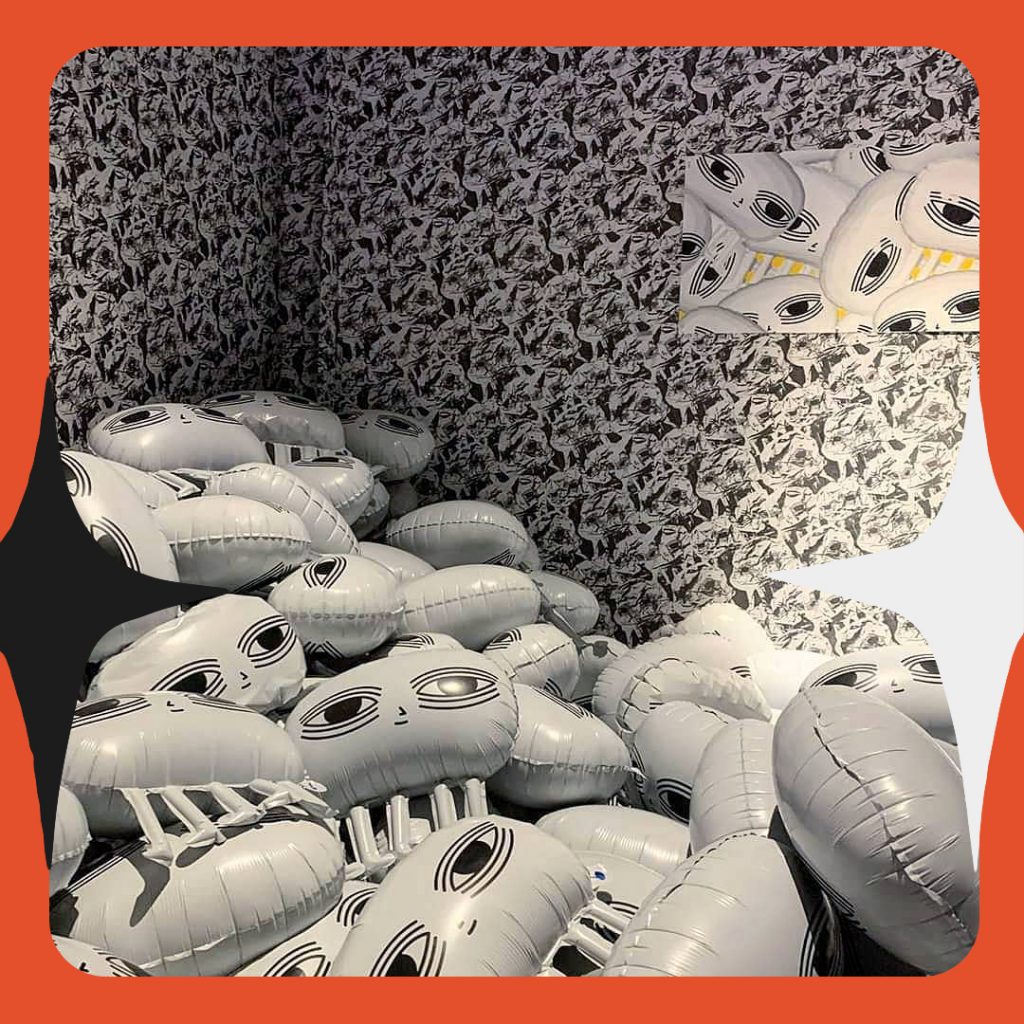

The wealthy millennial art patrons, newly minted by their big businesses and start ups, collects contemporary art with the same passion they collect street wear fashion, comic book figures, and retro video games. Inspired by the movements of street culture, skate, hip hop and graffiti, their style is loud and colorful, taking a leaf from the designs of brands like A Bathing Ape and Stüssy.

Their eclectic galleries and collections are where high art and pop culture collide to the tune of millions. Here, it wouldn’t be amiss to find a Quiccs x Adidas art toy, photojournalist exhibits of the on-going drug war, group exhibitions of tattoo artists, beside an Andres Barrioquinto piece.

Filipino artists have heard the Pied Piper’s new song and have deigned to follow. Artist Dex Fernandez and Distort Monsters, whose eye-catching street art first appeared in public spaces, have since held gallery exhibitions and churned out collectible merchandise. Fernandez’ iconic Garapata imagery have appeared on tote bags and face masks, Distort Monsters collaborated with US-based small appliance and electric fan manufacturer Vornado to come up with limited edition Artists’ Series for their energy smart air circulator. Even National Artist BenCab has partnered up with British audio equipment Rega Research to create a turntable featuring the artist’s painting “Sabel.” Only 100 pieces of this are available in the UK, and each was sold at P65,000.

These movements in the art scene and the art market show that Filipino contemporary art is in a state of flux. It is dynamic and alive, changing to fit both the larger Philippine society and the taste of its primary consumers. While there are efforts to increase awareness and appreciation of art among a broader audience, the luxury of owning and collecting art pieces is still very much tied to commerce.